(1.1) Two Athenian tales

(1.1.a) A horrid day to you, a good day to him

You are a Greek man of modest wealth living in Athens, 725 BC. You just had a good day, as far as you are concerned, but a day that would seem horrid to a 2015 American. On this day you threw a spear at your own brother to prevent him from leaving his ship and returning home. You love your brother, but doing your duty to your fellow Athenians is more important.

About this time last year it was becoming clear that the region was not producing enough food to feed everyone. Athens produced more food every year, but population grew faster. Some people had to leave. So for the fifth year in a row 250 citizens would depart in search of new lands to establish colonies. Your brother didn't want to go. He was just becoming a man and looked forward to marrying and entering political life. Athens went through the routine process of determining who would leave. They issued a call for volunteers and, as expected, those who answered the call were mostly young, adventurous men of little wealth, hoping to find a more promising future elsewhere. There was a problem though. None of these men were aristocrats, and there had to be at least one noble leading the group. The thought of an Athenian colony not led by a nobleman seemed absurd.

Figure 1—Ancient Greek

Settlements

The noblemen of Athens were asked to volunteer, but no one did, so the city set about deciding as a group, in its trademark democratic way, which nobleman would be forced to leave. They voted, and they voted to send your brother.

Being chosen was, in many ways, an honor. Athens wanted to be represented well, by a man of Greek strength and Greek values. A man with the strength and audacity of Heracles, a man who earned as much respect as Odysseus. They chose your brother because he was an Athenian to the bone, because he was young, and because he had not yet started a family.

I should add that your brother was also your best friend, and throughout the last year you have missed him deeply.

But when your brother left with his men he was forbidden to return. Again, he left because there was not enough food, and it was an insult to return and suggest that the little food that existed should be shared with him. Today he shamed himself by attempting to return home. He tried to explain from the boat that no suitable colony could be established. They either encountered hostile natives or infertile soils. Three-quarters of his men had already died of malnutrition, and you believed him, for he appeared to be a skeleton.

Still, it was your duty to ensure no colonist returned, and that is why you threw your spear; that is why you and your fellow citizens forced the colonists to turn their ship around and leave for the second time. From now on, if their boat appeared over the horizon, you promised him you would take a ship, hunt him down, and kill him yourself—this was not a threat, but a promise.

A difficult life requires difficult choices, like the one you made today. But you felt no guilt. It was not your fault Athens grew faster than its food supply. Something had to be done, and sending men away to establish colonies was, in your opinion, the best strategy. Moreover, you know you made the right choice, for as you walk home your fellow citizens congratulate you for your service. There is little time to stop for honors though, for your wife is giving birth.

(1.1.b) A horrid day to you, a good day to her

Now you are the wife giving birth, and you are filled with dread. Painful memories of the past two births haunt you. You already had one daughter, and your family simply couldn't have another. Girls were expensive, and with a limited food supply a family could only build wealth and pass it down through the generations if the family size was small and included a healthy male. When your first daughter was born you had to present it to your husband. On that day he looked down on that sweet little girl, and thought. It was his decision of whether the girl infant would be accepted into the family or left to die by exposure. He thought hard, and long. Although he decided to keep it, he made it clear that he would allow no more daughters. The next female infant would be left for the wild animals to take.

Indeed, in ancient Athens only one out of 100 families reared more than one daughter, and in some regions of Greece there were five sons for every daughter.

The second child was a son, which at first brought relief, until you looked at it closely. He didn't look right. His face was smashed flat, and one of his arms seemed slightly shorter than the other, but you were not sure. Although you didn't mention any of this you knew your husband saw the same thing when the child was presented to him. After looking at the child—his first infant son—he shook his head no, and the boy was taken, never to be seen again.

As you are giving birth you curse the soils and you curse the crowded city. If only there were more food, or less people, you could think of giving birth as a joyful occasion. Damn that dirt, damn these people.

Goddess Athena was kind that day, for you gave birth to a healthy son. When your husband rushed into the house, exhausted from his work that day, exhausted from his run, he smiled upon seeing the boy and nodded in the affirmative. You would keep this child.

(1.2) The Athenian problem

There was no political problem in Athens causing such suffering. No civil wars, no political instability, no wars with neighbors. The problem was agricultural, technological.

Surely, one would think that if Athens had the agricultural technology of today there would be no food shortage, and indeed, Greece today is a democracy going through a terrible economic recession, but no one is starving. Athens could only fertilize their fields with manure whereas we have factories that pull nitrogen out of the atmosphere and convert it into nitrogen fertilizer. A pest infestation could destroy an entire crop in ancient Athens, while we have synthetic pesticides that can deter almost any pest without threatening the safety of the food supply. Even organic farms who abstain from chemical fertilizers and pesticides have a great wealth of knowledge accumulated over centuries that allows them to be more productive than the ancient Athenian farmer. Ancient Athens harvested their grain by hand; we have combines.

Our advanced agricultural technologies allow us to easily feed the world, if the whole world had stable political democracies like Athens. Sadly, that is not the case.

(1.3) A Modern Tragedy

Below is a satellite picture of two countries taken at night. Look closely. Can you tell what these two countries are?

Figure 2—Satellite photo of two countries at night

When psychologists set about measuring the impact of nature versus nurture they usually study identical twins. If identical twins raised in different households behave differently, that is an indication that the environment is more important than genetics. Likewise, we can study the effect of economic systems by taking a homogeneous region, splitting it in half, and installing one economic system in one half and a different system in the other.

This picture shows the results of one of the largest experiments ever conducted. A single nation with a similar climate and culture in both the southern and northern part of the country were split in half after the Korean War. The northern half became a communist state ruled by an autocrat. The southern half became a capitalistic, representative democracy. Both countries have access to the same store of agricultural knowledge, the same agricultural technologies, and the same countries ready to befriend them and help them develop their agricultural sector.

Yet, as you can see from the picture, the capitalistic half is thriving, its brightly illuminated cities a symbol of its vibrant economic activity and wealth. The northern half seems basically dead, and indeed, death is something all too familiar in North Korea. In the latter half of the twentieth century North Korea confiscated all private property and made it the possession of the government. It no longer allowed people the freedom to choose their occupation, but forced them to work on government farms and government factories. It made trade illegal. Simply wanting to sell one‘s labor to buy some food became a crime.

Quotation 1—A historian on the failed North Korean state

The

failures of Communist economic policy had the most tragic consequences in

agriculture, the basis of the economy of nearly all countries subjected to

Communist rule. The confiscation of private property in land and the

collectivization that ensued disrupted traditional rural routines, causing

famines of unprecedented dimensions. This happened in the Soviet Union, China,

Cambodia, Ethiopia, and North Korea; in each country millions died from man-made

starvation. In Communist North Korea as late as the 1990s, a large proportion of

children suffered from physical disabilities caused by malnutrition; in the

second half of the 1990s, up to 2 million people are estimated to have died of

starvation there. Its infant mortality rate is 88 per 1,000 live births,

compared to South Korea’s 8, and the life expectancy for males is 48.9 years,

compared to South Korea’s 70.4. The GDP per capita in the north is $900; in

the south, $13,700.

—Pipes, Richard. 2001. Communism: A

History. Modern Library.

The world would love to offer North Korea humanitarian aid and to help it develop its agricultural sector to produce food efficiently. The scientific knowledge, the technological innovation, it is waiting for North Korea to take, and for free.

Figure 3—News

article on famine in North Korea

We all know why North Korea won't accept our charity. Because to farm as Americans farm requires American freedom: it requires private property and free markets (free markets meaning individuals are free to sell whatever goods they like at whatever price they can negotiate, with minimum interference from the government or individuals who wield power through force). American farmers are incredibly productive because of the scientific technologies available and their freedom to use the technologies however they like. Its citizens are of little concern to North Korean leaders though. They only care about power. Fearful it will lose its iron grip on its people, it would rather send its people into a famine every ten years than risk losing political power.

Figure 4—Feeding the

starving North Koreans

North Korea is the opposite of ancient Athens. If the political situation was better they could easily grow enough food. North Korea rejects everything American, because one way it maintains power is by depicting America as an aggressive enemy who is anxious to invade. Well, it doesn't reject everything American. It accepts Dennis Rodman. It also allows its people to read and watch Gone With the Wind, because it hopes its citizens, during times of hunger, will be inspired by these famous lines of Scarlett O'Hara.

Video 1—Inspiration for starving Koreans (from Gone With the Wind)

But think ... why was Scarlett O'Hara hungry. Was it because the soils of her estate are infertile? No. Was it because of a recent drought? No. Was it because the South was overpopulated? No. Why, then? Because of a political problem: the Civil War. If North Koreans identify with this scene I suspect it is not just their experience with hunger, but a government hell-bent on the destruction of others to maintain the power of a few.

Figure 5—This is how The Onion mocks North Korea

(1.4) I, American

We Americans have it made. We have a stable democracy similar to ancient Athens and access to the same agricultural technologies available to—though refused by —North Korea. We Americans are more likely to be obese than hungry. Food is not problem. You will spend much of your life trying to lose weight!

What is it about a society that requires there to be both democratic freedoms and knowledge to produce an abundant food supply? To answer that, consider this. Think of all the things that you will consume in a single day. All the foods, clothes, gasoline, automobiles, music, TV shows ... everything. Now consider all of those things that you produced yourself. Chances are, there was almost no overlap. Try and imagine how long it would take you to produce yourself all the things you consume in a day. A lifetime is not enough.

Figure 6—My

daughters’ toy collection is ridiculous

No matter how much one person knows about everything, including agriculture, place a person alone on a deserted island and they will be poor. Even if this island had books on all the knowledge in the world and a vast amount of natural resources, one person can do very little with it. Humans are an ultrasocial animal, like ants and bees. We need each other. Alone, a human is cursed with poverty and at the mercy of nature. Together with other humans, man can conquer nature.

You will spend most of your life producing things for other people. If you grow food, other people will eat most of it, not you. You produce these things for other people to earn money, and you then take that money and buy things made by other people. So virtually everything you consume is acquired by trade. The ability to freely trade with others is what makes us so wealthy and Robinson Crusoe, however smart or hard working he may be, poor.

Understanding how to feed a large population does require plant science, and it does require animal science. It requires sophisticated tractors, fertilizers made in factories, and new genetic varieties of crops and animals. But it also requires an economic and political system that allows and even encourages voluntary trade between people, and most of the times these trades are between strangers. And that is what economics is about: trade. It is about how a social system allows you to consume goods produced by strangers in far greater quantities than you could ever produce yourself. Our great wealth derives ultimately from our ability to make profits by creating things for other people, and using those profits to buy things made from other people. Our great wealth derives ultimately from free-trade. After all, agricultural technologies like combines, new seed varieties, and chemical fertilizers are mostly invented by people pursuing profits.

Figure 7—Frederic Bastiat (1801-1850), French Economist and Journalist

Bastiat pic.jpg)

Quotation 2—From Bastiat’s book Economic Harmonies

Let us take, by way of illustration, a man in the humble walks of life—a village carpenter, for instance—and observe the various services he renders to society, and receives from it; we shall not fail to be struck with the enormous disproportion that is apparent.

This man employs his day’s labor in planing boards, and making tables and chests of drawers. He complains of his condition; yet in truth what does he receive from society in exchange for his work?

First of all, on getting up in the morning, he dresses himself; and he has himself personally made none of the numerous articles of which his clothing consists.

Now, in order to put at his disposal this clothing ... Americans must have produced cotton, Indians indigo, Frenchmen wool and flax, Brazilians hides; and all these materials must have been transported to various towns where they have been worked up, spun, woven, dyed, etc.

Then he breakfasts. In order to procure him the bread he eats every morning, land must have been cleared, enclosed, labored, manured, sown; the fruits of the soil must have been preserved with care from pillage, and security must have reigned among an innumerable multitude of people; the wheat must have been cut down, ground into flour, kneaded, and prepared; iron, steel, wood, stone, must have been converted by industry into instruments of labor; some men must have employed animal force, others water power, etc.; all matters of which each, taken singly, presupposes a mass of labor, whether we have regard to space or time, of incalculable amount.

In the course of the day this man will have occasion to use sugar, oil, and various other materials and utensils.

He sends his son to school, there to receive an education, which, although limited, nevertheless implies anterior study and research, and an extent of knowledge that startles the imagination.

He goes out. He finds the street paved and lighted.

A neighbor sues him. He finds advocates to plead his cause, judges to maintain his rights, officers of justice to put the sentence in execution; all which implies acquired knowledge, and, consequently, intelligence and means of subsistence.

He goes to church. It is a stupendous monument, and the book he carries thither is a monument, perhaps still more Stupendous, of human intelligence.

He is taught morals, he has his mind enlightened, his soul elevated; and in order to do this we must suppose that another man had previously frequented schools and libraries, consulted all the sources of human learning, and while so employed had been able to live without occupying himself directly with the wants of the body.

If our artisan undertakes a journey, he finds that, in order to save him time and exertion, other men have removed and levelled the soil, filled up valleys, hewed down mountains, united the banks of rivers, diminished friction, placed wheeled carriages on blocks of sandstone or bands of iron, and brought the force of animals and the power of steam into subjection to human wants.

It is impossible not to be struck with the measureless disproportion between the enjoyments which this man derives from society and what he could obtain by his own unassisted exertions. I venture to say that in a single day he consumes more than he could himself produce in ten centuries.

...

The social mechanism, then, must be very ingenious and very powerful, since it leads to this singular result, that each man, even he whose lot is cast in the humblest condition, has more enjoyment in one day than he could himself produce in many ages.

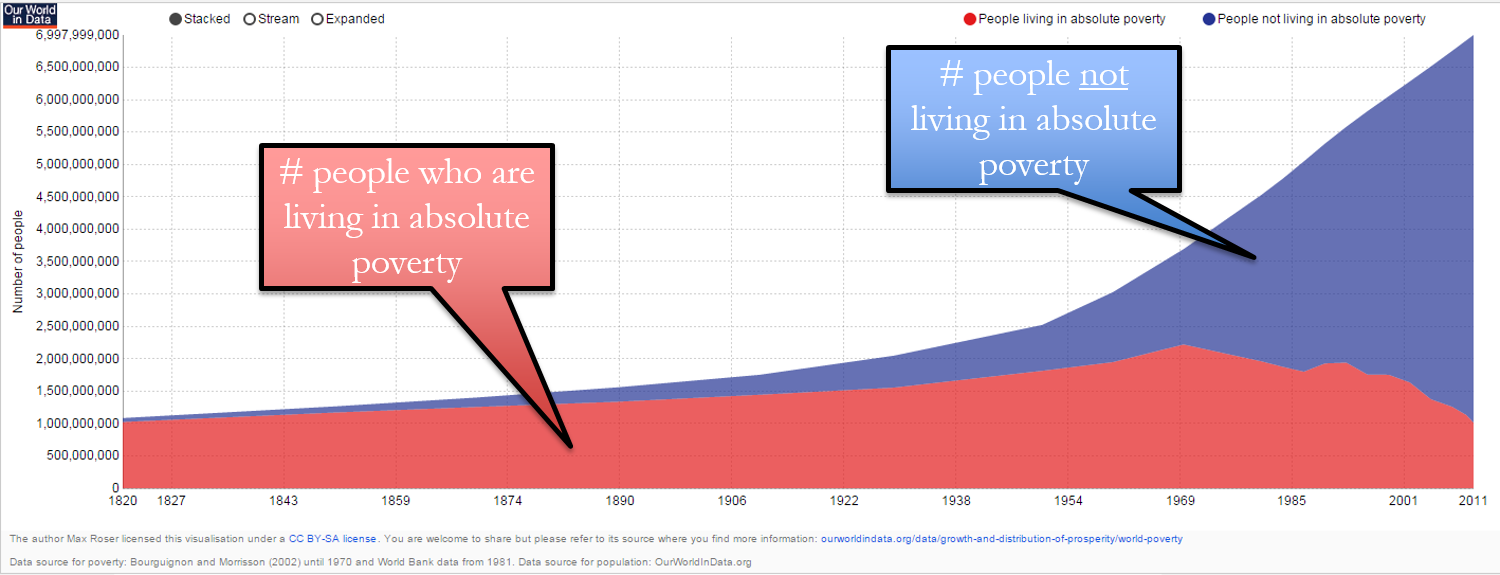

Good gravy, just look at what this thing we call capitalism has done to enrich the world. For the vast majority of human history the average wealth (measured in 1990 U.S. dollars) was less than $400 a year. Then in the Early Modern Age (around 1500) capitalism began to develop in western Europe. When this capitalism evolved into the Industrial Revolution around 1800, the countries that experienced it (U.S., Western Europe, Japan) surged in prosperity. This Industrial Revolution was a generous blend of technological innovation taking place in societies allowing private property and free markets. It was because of property and free markets that innovation was especially profitable, and it was the pursuit of profits that led to the innovations. The result has been an explosion of wealth, and when it was later adopted in China and India in the 1950s, they realized wealth gains also.

Figure 8—Show me the money!

An economic system fostering free trade and technological advancement requires a certain political system, like the systems in the U.S. and western Europe. This is a system that protects property, gives people the right to trade that property at whatever price they can negotiate, and preserves the peace. Today, scarcity of food is not a weather or technological problem—it is a political problem. Wherever you find starving people you will find a repressive political regime.

Figure 9—This will break your heart

Economics, ultimately, is about a free, harmonious society. Economics teaches us that our social interactions are not a zero-sum games, where the only way for me to gain in wealth is to take the wealth of others. No, by living in a free society with private property and markets we can all grow wealthier at the same time. Under the right conditions, our social interactions can be a positive-sum game. Are we not much, much wealthier than the ancient Greeks?

Figure 10—It

sounds corny, but economics is about social harmony

Yes, we are, and to continue to grow in wealth requires you to understand these concepts we call free-trade, markets, supply and demand and the like. Given that this is what makes us different than North Korea, I cannot think of a more important subject to study.

Economics is about economics, and culture, and ethics, and politics, and ...

We have seen that our modern wealth is due to technology, private property, and free markets, among other things. These three items are not independent of one another though. Private property is most valuable when there are free markets, as land is more valuable when we are free to sell what the land produces. Free markets requires private property, because to sell something you must own it in the first place, and no one wishes to buy anything unless it bestows them with ownership. Finally, technological progress depends private property and free markets. Most of the agricultural innovations in the last few decades were not produced out of altruism, but the pursuit of profits. Fertilizers and tractors are perhaps the greatest inventions in the history of the world, but were not created solely out of love for mankind.

Private property, free markets, and technological innovation require a certain political and cultural environment to thrive, and this implies that economics concerns both politics and culture. China began prospering in the 1950s because they adopted capitalistic public policies, such as allowing individuals to own their own land, produce whatever they like from the land, buy farm inputs at prices they negotiate, and sell farm output at prices they negotiate. Developing a favorable economy requires first having a good political system. Economics is about politics.

Societies were held back for many years by a cultural disapproval of earning profits. Business people used to be seen as among the lower rungs of societies, and it was demeaning for an aristocrat to conduct business. In ancient Greece and Rome important political leaders were often prohibited from conducting business, and the following line from The Hunchback of Notre Dame shows that business used to be a dishonorable occupation.

Quotation 3—From Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Comrade! you have the air of a merchant of tennis-balls; and you come and sit yourself beside me! I am a nobleman, my friend! Trade is incompatible with nobility.

—Hugo, Victor. 1831. The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The setting of the story is 15th century France.

Today we admire successful but ethical business people, and business is one of the most popular subjects to study at college. This helps ensure that many of our most talented individuals enter the business world, joining in this positive-sum game that has made us so wealthy. When economists seek to identify the most important sources of our wealth, they often conclude that our cultural approval of ethical business people to be the most important one.

All of this is to say that we study economics because we need to both preserve the government policies and the cultural norms that have made us the wealthiest humans to have ever lived.

The modern world is not just or kind, but it is a much better place than it used to be. We also want it to be better than it is. The chart testifies that we are making progress on our road to Utopia. Let that progress continue, and let it begin with studying economics.

Quotation 4—Look at all the happy people!

Even North Korea realizes this now

The North Korean government may be malevolent but they are not stupid. The wealth in modern capitalistic democracies and the rising living standards in China has made it clear to them that private property and free markets are needed for an adequate food supply, and so in the last twenty it has made a number of adjustments. The average citizen has an official government job, but it makes them little money and they avoid working in it. Bribes are paid so that they don’t have to show up, and they often claim medical problems. They avoid their official government job because they spend as much time as possible in their private jobs where they buy and sell things and engage in economic production to make money. Most of the food they eat, and most of the money they spend, come from these illegal private jobs, not their official government ones.

Figure 11—Capitalism in North Korea

Officially there is no private property, and officially market trading are illegal, but the government has decided to look the other way, and usually charge money for looking the other way. In fact, a successful business generally has to pay government officials 30-40% of its profits for the right not to be arrested. Why does the Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un allow this? Because some of that money finds its way to him. North Koreans grow food and sell it in farmers markets. They import goods illegally, and sell them on the black market. They produce goods in buildings resembling factories, and even export.

Like the U.S., most of what North Korea consumes is due to technology, private property, and free markets. The only reason is that since property and market trading is illegal it is very costly, and so less of it than in the U.S. Consequently, there is less of everything compared to the U.S., except misery.

References not mentioned

Garland, Robert. The Other Side of History: Daily Life in the Ancient World. The Great Courses.

Sullivan, Tim. October 2013. “Now You See It.” National Geographic magazine.

Tudor, Daniel and James Pearson. 2015. North Korea Confidential. Tuttle PUblishing.